By December of 1620, after a long Atlantic voyage, the English Separatist William

Bradford and his crew had explored several landing spots along the North American

coast. They’d rejected various locations after having conflicts with indigenous people.

Finally, according to legend, Bradford and his party disembarked on a large boulder,

which would eventually be known as Plymouth Rock. They soon declared the

surrounding area suitable for their New World settlement, Plymouth Colony.

Although the rock has much historical significance, evidently none of the Pilgrims

mentioned it in their writings. Knowledge of its location was traditionally passed from

parents to their children. In 1741, the 94-year-old Elder Faunce identified Plymouth Rock

as the stone his father had pointed out years earlier. Faunce was a somewhat credible

source; he had been Plymouth’s record keeper for many decades. Still, his father had not

been among the original Plymouth settlers; he’d arrived three years later in 1623 and

heard the Plymouth Rock story from others. Nevertheless, people accepted Faunce’s

story and the identified rock took on great patriotic significance.

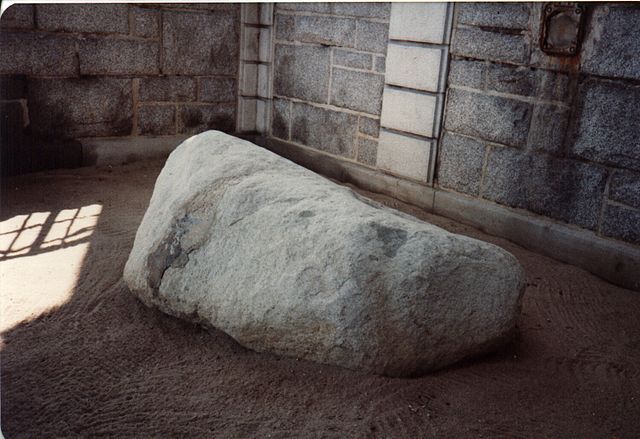

It’s estimated that the rock weighed about 20,000 pounds when Bradford and 101 other

Mayflower passengers left their ship in 1620. Since then, the rock has lost many sections

to souvenir-hunters. It’s also been accidentally split in two and eventually reunited.

How did Plymouth Rock become split? In 1774, as the Revolutionary spirit took over in

Massachusetts Bay Colony, a group of people “animated by the glorious spirit of liberty”

intended to move the entire rock to the Plymouth Meeting House. Colonel Theopolis

Cotton and a group of “Liberty Boys” prepared a carriage drawn by oxen. As they pulled

the rock from the ground, it was unintentionally cracked it in two!

Superstitious townspeople believed the divided rock was symbolic of the British Empire.

They left the “British half” of the rock in the water. Only the top “liberty half” of the rock

was then moved. It soon rested beneath a Meeting House flagpole and a flag that declared

“Liberty or Death”. The remainder of the rock stayed embedded in the wharf. The next

year, a colonial revolutionary would capture British soldiers and, for his amusement,

have them step onto Plymouth Rock, a symbol of American independence.

The two parts of the rock have experienced a few changes since the 1774 division. In

1834, the top section of the rock was removed to Pilgrim Hall (a museum) and put under

the auspices of the historical Pilgrim Society. In 1859, the Pilgrim Society began building

a Victorian canopy to cover the piece of rock left at the wharf. The canopy was

completed in 1867. Since many bits of the rock were being taken by travelers and

shopkeepers for profit, an iron gate was soon erected. In 1880 the top of the rock was

moved back to shore and affixed to the bottom portion with cement. At this time, the

landing date 1620 was carved.

In 1920 the rock was moved yet again. In honor of the 300th anniversary of the Plymouth

Rock landing, the entire Plymouth waterfront was redesigned with a promenade and

seawall. The cemented rock was moved to the waterfront and a portico was erected for

viewers. Today the rock is managed as part of Pilgrim Memorial State Park. Tourists can

visit the rock for free year-round. From May through Thanksgiving, staff members are on hand to tell visitors about Plymouth Rock’s history.

Discover more from LandmarkLocation.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.