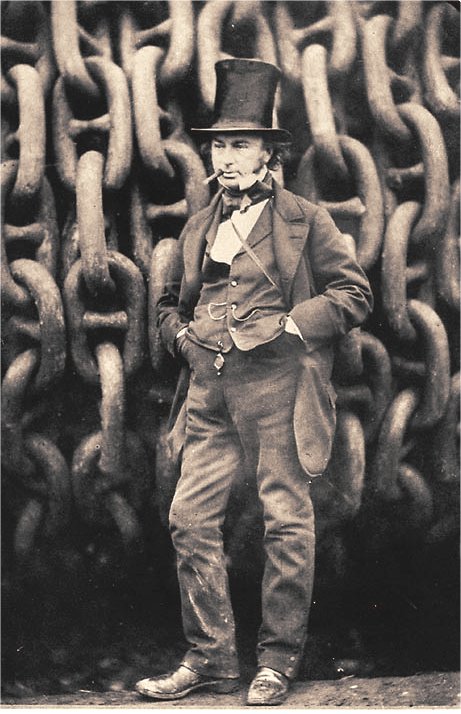

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, FRS (9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859), was a British engineer. He is best known for the creation of the Great Western Railway, a series of famous steamships, including the first with a propeller, and numerous important bridges and tunnels. His designs revolutionised public transport and modern day engineering.

Though Brunel’s projects were not always successful, they often contained innovative solutions to long-standing engineering problems. During his short career, Brunel achieved many engineering “firsts”, including assisting in the building of the first tunnel under a navigable river and development of SS Great Britain, the first propeller-driven ocean-going iron ship, which was at the time also the largest ship ever built. His steamship the SS Great Eastern laid the first lasting telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean.

Brunel suffered several years of ill health, with kidney problems, before succumbing to a stroke at the age of 53 years. Brunel was said to smoke up to 40 cigars a day and to sleep as little as four hours each night.

In 2006, the bicentenary of his birth, a major programme of events celebrated his life and work under the name Brunel 200.

Early life

The son of the engineer Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, an exiled Frenchman, and Sophia (née Kingdom) Brunel (d. 1854), Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on 9 April 1806. His father was working there on block-making machinery for the Portsmouth Block Mills.

At the age of 14 years Brunel was sent to France to be educated at the Lycée Henri-Quatre in Paris and the University of Caen in Normandy. When Brunel was 15 years of age, his father, Marc Brunel, was sent to a debtors prison for debts of over £5000. These were mostly paid by the government to prevent this eminent engineer defecting to Russia. Isambard was therefore able to continue his studies in France.

Brunel rose to prominence when, aged 20, he was appointed chief assistant engineer of his father’s greatest achievement, the Thames Tunnel, which runs beneath the river between Rotherhithe and Wapping.

The first major sub-river tunnel, it succeeded where other attempts had failed, thanks to Marc Brunel’s ingenious tunnelling shield – the human-powered forerunner of today”s mighty tunnelling machines – which protected workers from cave-in by placing them within a protective casing. Marc Brunel had been inspired to create the shield after observing the habits and anatomy of the shipworm, Teredo navalis.

Most modern tunnels are cut in this way, notably the Channel Tunnel between southern England and France.

Brunel established his design offices at 17-18 Duke Street, London, and he lived with his family in the rooms above.

On 5 July 1836, Brunel married Mary Elizabeth Horsley (b. 1813), the eldest daughter of composer and organist William Horsley, who came from an accomplished musical and artistic family.

R.P. Brereton, who became his chief assistant in 1845, was in charge of the office in Brunel’s absence, and also took direct responsibility for major projects such as the Royal Albert Bridge as Brunel”s health declined.

Thames Tunnel

Brunel worked for nearly two years to create a tunnel under London’s River Thames, with tunnellers driving a horizontal shaft from one side of the river to the other under the most difficult and dangerous conditions. Brunel’s father, Marc, was the chief engineer, and the project was funded by the Thames Tunnel Company. The composition of the Thames river bed at Rotherhithe was often little more than waterlogged sediment and loose gravel, and although the extreme conditions proved the ingenuity of Brunel’s tunnelling machine, the work was hard and hazardous.

For the workers the building of the tunnel was particularly unpleasant because the Thames at that time was still little better than an open sewer, so the tunnel was usually awash with foul-smelling, contaminated water. The tunnel was often in imminent danger of collapse due to the instability of the river bed, yet the management decided to allow spectators to be lowered down to observe the diggings at a shilling a time. Two severe incidents of flooding halted work for long periods, killing several workers and badly injuring the younger Brunel.

The later incident, in 1828, killed the two most senior miners, Collins and Ball, and Brunel himself narrowly escaped death; a water break-in hurled him from a tunnelling platform, knocking him unconscious, and he was washed up to the other end of the tunnel by the surge. As the water rose, by luck he was carried up a service stairway, where he was plucked from almost certain death by an assistant moments before the surge receded. Brunel was seriously hurt (and never fully recovered from his injuries), and the event ended work on the tunnel for several years.

Originally designed for pedestrians, the tunnel was converted to accommodate the East London Railway in 1869 and became part of the London Underground East London Line between Rotherhithe and Wapping in 1933. It was closed in December 2007 to be converted for use by the London Overground system and is due to reopen in 2010. The building that contained the pumps to keep the Thames Tunnel dry was saved from demolition in the 1970s by volunteers and made a Scheduled Ancient Monument and grade two listed building. It now houses the Brunel Museum, which documents not just the Thames Tunnel but also Marc and Isambard”s many other achievements. The Thames tunnel is open to the public during September each year as part of the Open House London Weekend. Free-of-charge tube trains, travelling at creep speed, journey through the tunnel, and guides point out the remnants of the world”s first shopping mall. Vendors used to trade in the arches built along its length.

Bridges

Brunel’s solo engineering feats started with bridges- the Royal Albert Bridge spanning the River Tamar at Saltash near Plymouth, and an unusual timber-framed bridge near Bridgwater.

Brunel’s oldest wrought iron bridge is the Windsor Railway Bridge, which was opened in 1849.

Built in 1838, the Maidenhead Railway Bridge over the Thames in Berkshire was the flattest, widest brick arch bridge in the world and is still carrying main line trains to the west. There are two arches, with each span totalling 128 ft (39 m), having a rise of only 24 ft (7 m), and a width that carries four tracks. The rather flat arches reduce the difficulty railway engines have with steep gradients (especially on hump-back bridges) and today”s trains are about 10 times as heavy as Brunel ever imagined.

In 1845 Hungerford Bridge, a suspension footbridge across the River Thames, near Charing Cross Station in London, was opened only to be replaced by a new railway bridge in 1859.

Brunel had to overcome many obstacles throughout his years as an engineer. For example, he had to halt work on the Clifton Bridge due to the arrival of Sir Charles Wetherall in Clifton. There were numerous riots and they drove away investors leaving no money for Brunel to work with.

Throughout his railway building, but particularly on the South Devon and Cornwall Railways where economy was needed and there were many valleys to cross, Brunel made extensive use of wood for the construction of substantial viaducts; these have had to be replaced over the years.

The Royal Albert Bridge was designed in 1855 for the Cornwall Railway Company, after Parliament rejected his original plan for a train ferry across the Hamoaze- the estuary of the tidal Tamar, Tavy and Lynher. The bridge (of bowstring girder or tied arch construction) consists of two main spans of 455 ft (139 m), 100 ft (30 m) above mean high spring tide, plus 17 much shorter approach spans. Opened by Prince Albert on 2 May 1859, it was completed in the year of Brunel”s death.

However, Brunel is perhaps best remembered for the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. Spanning over 700 ft (213 m), and nominally 200 ft (61 m) above the River Avon, it had the longest span of any bridge in the world at the time of construction. Brunel submitted four designs to a committee headed by Thomas Telford and gained approval to commence with the project. Afterwards, Brunel wrote to his brother-in-law, the politician Benjamin Hawes: “Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject- taste”. He did not live to see it built, although his colleagues and admirers at the Institution of Civil Engineers felt the bridge would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds and to amend the design. Work started in 1862 and was complete in 1864, five years after Brunel’s death. The Clifton Suspension Bridge still stands strong today. It supports approximately 4 million cars crossing the River Avon every year. The 50 pence toll it costs to cross helps to pay for upkeep and repairs on the bridge.

In 2006, there is the possibility that several of Brunel’s bridges over the Great Western Railway might be demolished because the line is planned to be electrified, and there is inadequate clearance for the overhead wires. Buckinghamshire County Council is petitioning to have further options pursued, in order that all nine of the historic remaining bridges on the line can remain.

Great Western Railway

In the early part of Brunel’s life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel’s involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway, one of the wonders of Victorian Britain, running from London to Bristol and later Exeter. The Company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833, and was incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1835. It was Brunel’s vision that passengers would be able to purchase one ticket at London Paddington and travel from London to New York, changing from the Great Western Railway to The Great Eastern Steamship at the Terminus in Neyland, South Wales.

Brunel made two controversial decisions: to use a broad gauge of 7 ft 0¼ in (2,140 mm) for the track, which he believed would offer superior running at high speeds; and to take a route that passed north of the Marlborough Downs, an area with no significant towns, though it offered potential connections to Oxford and Gloucester and then to follow the Thames Valley into London. His decision to use broad gauge for the line was controversial in that almost all British railways to date had used standard gauge. Brunel said that this was nothing more than a carry-over from the mine railways that George Stephenson had worked on prior to making the world”s first passenger railway. Brunel worked out through mathematics and a series of trials that his broader gauge was the optimum railway size for providing stability and a comfortable ride to passengers, in addition to allowing for bigger carriages and more freight capacity. The broad gauge also allowed higher speeds. He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself.

Drawing on his experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements- soaring viaducts, specially designed stations, and vast tunnels including the famous Box Tunnel, which was the longest railway tunnel in the world at that time.

There is an anecdote that Box Tunnel is so oriented that the sun shines all the way through it on Brunel’s birthday.

The initial group of locomotives ordered by Brunel to his own specifications proved unsatisfactory, apart from the North Star locomotive, and 20-year-old Daniel Gooch (later Sir Daniel) was appointed as Superintendent of Locomotives. Brunel and Gooch chose to locate their locomotive works at the village of Swindon, at the point where the gradual ascent from London turned into the steeper descent to the Avon valley at Bath.

Brunel’s achievements ignited the imagination of the technically minded Britons of the age, and he soon became one of the most famous men in the country on the back of this interest.

After Brunel’s death the decision was taken that standard gauge should be used for all railways in the country. Despite the Great Western”s claim of proof that its broad gauge was the better (disputed by at least one Brunel historian), the decision was made to use Stephenson”s standard gauge, mainly because this had already covered a far greater amount of the country. However, by May 1892 when the broad gauge was abolished the Great Western had already been re-laid as dual gauge (both broad and standard) and so the transition was a relatively painless one. At the original Welsh terminus of the Great Western railway at Neyland, sections of the broad gauge rails are used as handrails at the quayside, and a number of information boards here depict various aspects of his life. There is also a larger than life bronze statue of him holding a steamship in one hand and a locomotive in the other.

The present Paddington station was designed by Brunel and opened in 1854. Examples of his designs for smaller stations on the Great Western and associated lines which survive in good condition include Mortimer, Charlbury and Bridgend (all Italianate) and Culham (Tudorbethan). Surviving examples of wooden train sheds in his style are at Frome and Kingswear.

The great achievement that was the Great Western Railway has been immortalised in the Swindon Steam Railway Museum.

Overall, there were negative views as to how society viewed the railways. Some landowners felt the railways were a threat to amenities or property values and others requested tunnels on their land so the railway could not be seen.

Brunel’s “atmospheric caper”

Though ultimately unsuccessful, another of Brunel’s interesting use of technical innovations was the atmospheric railway, the extension of the GWR southward from Exeter towards Plymouth, technically the South Devon Railway (SDR), though supported by the GWR. Instead of using locomotives, the trains were moved by Clegg and Samuda’s patented system of atmospheric (vacuum) traction, whereby stationary pumps sucked air from the tunnel.

The section from Exeter to Newton (now Newton Abbot) was completed on this principle, with pumping stations with distinctive square chimneys spaced every two miles, and trains ran at approximately 20 miles per hour (30 km/h). Fifteen-inch (381 mm) pipes were used on the level portions, and 22-inch (559 mm) pipes were intended for the steeper gradients.

The technology required the use of leather flaps to seal the vacuum pipes. The leather had to be kept supple by the use of tallow, and tallow is attractive to rats. The result was inevitable- the flaps were eaten, and vacuum operation lasted less than a year, from 1847 (experimental services began in September; operationally from February 1848) to 10 Septembr 1848.

The accounts of the SDR for 1848 suggest that atmospheric traction cost 3s 1d (three shillings and one penny) per mile compared to 1s 4d/mile for conventional steam power. A number of South Devon Railway engine houses still stand, including that at Totnes (scheduled as a grade II listed monument in 2007 to prevent its imminent demolition, even as Brunel”s bicentenary celebrations were continuing) and at Starcross, on the estuary of the River Exe, which is a striking landmark, and a reminder of the atmospheric railway, also commemorated as the name of the village pub.

A section of the pipe, without the leather covers, is preserved at the Didcot Railway Centre.

Transatlantic Shipping

Even before the Great Western Railway was opened, Brunel was moving on to his next project: transatlantic shipping. He used his prestige to convince his railway company employers to build the Great Western, at the time by far the largest steamship in the world. Great Western first sailed in 1837.

She was 236 ft (72 m) long, built of wood, and powered by sail and paddle wheels. Her first return trip to New York City took just 29 days, compared to two months for an average sailing ship. In total, 74 crossings to New York were made.

The Great Britain followed in 1843; much larger at 322 ft (98 m) long, she is considered the first modern ship, in that she was built of metal rather than wood, was powered by an engine rather than wind or oars, and driven by propeller rather than paddle wheel. She was the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Brunel was a strong proponent of propellers for ships, and the Royal Navy commissioned him to prepare a test for proof of the propeller”s superior propulsion method compared with the paddle wheels of that time.[citation needed] Brunel fitted two identical tugs of the same engine and power, one with paddle wheels and the other with a propeller, and staged a “tug of war” with two tugs pulling a rope on the Thames river in England.[citation needed] The propeller driven HMS Rattler was further challenged by having to pull the rival tug boat upstream,[citation needed] yet the propeller driven tug boat won and the Royal Navy was convinced propellers were more efficient.

In 1852 Brunel turned to a third ocean-going ship, even larger than both of her predecessors, and intended for voyages to India and Australia. The Great Eastern (originally dubbed Leviathan) was cutting-edge technology for her time: almost 700 ft (213 m) long, fitted out with the most luxurious appointments and capable of carrying over 4,000 passengers.

She was designed to be able to cruise under her own power non-stop from London to Sydney and back since engineers of the time were under the misapprehension that Australia had no coal reserves, and she remained the largest ship built until the turn of the century. Like many of Brunel’s ambitious projects, the ship soon ran over budget and behind schedule in the face of a series of momentous technical problems.

The ship has been portrayed as a white elephant, but it can be argued that in this case Brunel”s failure was principally one of economics- his ships were simply years ahead of their time. His vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, screw-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry.

Great Eastern was built at John Scott Russell’s Napier Yard in London, and after two trial trips in 1859, set forth on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 17 June 1860.

Though a failure at her original purpose of passenger travel, she eventually found a role as an oceanic telegraph cable-layer, and the Great Eastern remains one of the most important vessels in the history of shipbuilding- the Trans-Atlantic cable had been laid, which meant that Europe and America now had a telecommunications link.

Crimean War

During 1854, Britain entered into the Crimean War, and an old Turkish Barrack building became the British Army Hospital in Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul). With injured men suffering from a variety of illnesses including cholera, dysentery, typhoid and malaria purely from hospital conditions, Florence Nightingale sent a plea to The Times for the government to produce a solution.

Brunel was already working on building the SS Great Eastern amongst other projects, but accepted the task in February 1855 of designing and building the War Office requirement of a temporary, pre-fabricated hospital that could be shipped to the Crimea and erected. In 5 months he had designed, built and shipped the pre-fabricated wood and canvas buildings that were erected near Scutari Hospital where Nightingale was based, in the malaria-free area of Renkioi.

His designs incorporated the necessity of hygiene, providing access to sanitation, ventilation, drainage and even rudimentary temperature controls. They were feted as a great success, some sources stating that of the 1,300 (approximate) patients treated in the Renkioi temporary hospital, there were only 50 deaths. In the Scutari hospital it replaced, deaths were said to be as many as 10 times this number. Nightingale herself referred to them as “those magnificent huts.” Brunel not only designed the buildings but gave advice as to the location of placing.

The art of using pre-fabricated modules to build hospitals has been carried forward into the present day, with hospitals such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary being created in this manner.

Illnesses and death of Brunel

In 1843, while performing a conjuring trick for the amusement of his children, Brunel accidentally inhaled a half-sovereign coin, which became lodged in his windpipe. A special pair of forceps failed to remove it, as did a machine devised by Brunel himself to shake it loose.

Eventually, at the suggestion of Sir Marc, Brunel was strapped to a board and turned upside-down, and the coin was jerked free. He recuperated by visiting Teignmouth and enjoyed the area so much that he purchased an estate at Watcombe in Torquay, Devon. Here he designed Brunel Manor and its gardens to be his retirement home. Unfortunately he never saw the house or gardens finished, as he died before it was completed.

Brunel suffered a stroke in 1859, just before the Great Eastern made her first voyage to New York. He died ten days later at the age of 53 and was buried, like his father, in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

He left behind his wife Mary and three children: Isambard Brunel Junior (1837-1902), Henri Marc Brunel (1842-1903) and Florence Mary Brunel (1847-1876). Henri Marc enjoyed some success as a civil engineer.

Legacy

As a celebrated engineer in his own time, Brunel is much revered to this day, emphasised by the numerous monuments to him. There are statues in London at Temple (pictured) and Brunel University, Bristol, Saltash, Swindon, Milford Haven, Neyland and Paddington station. The flagpole of the Great Eastern is at the entrance to Liverpool FC, and a section of the ship”s funnel is at Sutton Poyntz, near Weymouth. Brunel was placed second in the heavily publicised “100 Greatest Britons” TV poll conducted by the BBC and voted for by the public. In the second round of voting, which concluded on 24 November 2002, Brunel was placed second, behind Winston Churchill. The building of the Great Eastern was dramatised in an episode of the BBC TV series Seven Wonders of the Industrial World (2003).

Brunel is also often claimed to be the inventor of the Bar (counter) as an item of furniture for quickly serving large numbers of customers in cafes, refreshment rooms, hotels and public houses. Both the Great Western Hotel at Paddington Station and the Swindon railway station refreshment rooms claim to have had the world”s first bar. This device continues to remain popular all over the world.

Contemporary locations bear Brunel”s name, such as Brunel University in London, and a collection of streets in Exeter: Isambard Terrace, Kingdom Mews, and Brunel Close. A road, car park and school in his home town of Portsmouth are also named in his honour, along with the town”s largest pub. Although not of any real architectural merit, the Brunel shopping centre in Bletchley, Milton Keynes is named after him.

Many of Brunel’s bridges are still in use; these designs have stood the test of time. Brunel’s first engineering project the Thames Tunnel is to become part of the East London Overground Railway System and the Brunel Engine House at Rotherhithe that once housed the steam engines that powered the tunnel pumps still stands as a museum dedicated to the work and lives of Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Many of Brunel’s original papers and designs are now held in the Brunel collection at the University of Bristol.

Brunel is credited with turning the town of Swindon into one of the largest growing towns in Europe during the 1800s. The siting of the Great Western Railway locomotive sheds there and the need for housing for the workers, gave Brunel the impetus to build hospitals, churches and housing estates in what was termed ”New Swindon” (subsequently swallowed by the rest of the expanding, mainly agricultural, town). This area is known today as the ”Railway Village”. Brunel’s addition of a Mechanics Institute for recreation and hospitals and clinics for his workers gave Aneurin Bevan the basis for the creation of the National Health Service according to some sources. The current hospital in Swindon was named the Great Western Hospital in commemoration, which also contains the ”Brunel Treatment Centre”.

In 2006, the Royal Mint struck a £2 coin to “celebrate the 200th anniversary of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his achievements”. The coin depicts a section of the Royal Albert Bridge at Saltash, along with a portrait of Brunel. The Post Office issued a set of commemorative stamps. For the 100-year anniversary of the Royal Albert Bridge the words “I.K. BRUNEL ENGINEER 1859” was engraved on either end of the bridge to commemorate the legacy that is Isambard Kingdom Brunel.