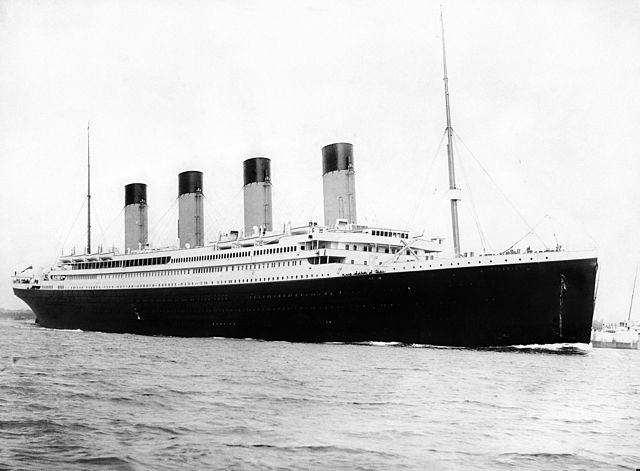

RMS Titanic was an Olympic-class passenger liner owned by the White Star Line and built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland (now Northern Ireland). On the night of 14 April 1912, during her maiden voyage, Titanic hit an iceberg, and sank two hours and forty minutes later, early on 15 April 1912. At the time of her launching in 1912, she was the largest passenger steamship in the world.

The sinking resulted in the deaths of 1,517 people, ranking it as one of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in history and by far the most famous. The Titanic used some of the most advanced technology available at the time and was, prior to the sinking, popularly believed to be “unsinkable”. It was a great shock to many that despite the advanced technology and experienced crew, the Titanic sank with a great loss of life. The media frenzy about Titanic”s famous victims, the legends about what happened on board the ship, the resulting changes to maritime law, and the discovery of the wreck in 1985 by a team led by Robert Ballard have made Titanic persistently famous in the years since.

Construction

The Titanic was a White Star Line ocean liner, built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland, and designed to compete with the rival Cunard Line”s Lusitania and Mauretania. The Titanic, along with her Olympic-class sisters, the Olympic and the soon to be built Britannic (originally named Gigantic), were intended to be the largest, most luxurious ships ever to operate.

Construction of RMS Titanic, funded by the American J.P. Morgan and his International Mercantile Marine Co., began on 31 March 1909. Titanic’s hull was launched on 31 May 1911, and her outfitting was completed by 31 March the following year.

Titanic was 882 ft 9 in (269 m) long and 92 ft 6 in (28 m) wide, with a gross register tonnage of 46,328 tons and a height from the water line to the boat deck of 60 ft (18 m). She contained two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion, inverted steam engines and one low-pressure Parsons turbine, which powered three propellers. There were 29 boilers fired by 159 coal burning furnaces that made possible a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h). Only three of the four 63-feet (19 m) tall funnels were functional; the fourth, which served only as a vent, was added to make the ship look more impressive. The ship could carry a total of 3,547 passengers and crew and, because she carried mail, her name was given the prefix RMS (Royal Mail Steamer) as well as SS (Steam Ship).

Lifeboats

Alexander Carlisle, one of Harland and Wolff’s managing directors, suggested that Titanic use a new, larger type of davit which could give the ship the potential to carry 48 lifeboats; this would have provided enough seats for everyone on board. However, the White Star Line decreed that only 20 lifeboats would be carried, which could accommodate only 52% of the people aboard. At the time, the Board of Trade’s regulations stated that British vessels over 10,000 tons must carry 16 lifeboats with a capacity of 5,500 cubic feet plus enough rafts and floats for 75% of the lifeboats. Therefore, the White Star Line actually provided more lifeboat accommodation than was legally required.

The lifeboats comprised 16 wooden lifeboats, each 30 ft (9.1 m) long by 9 ft 1 in (2.8 m) wide, with a capacity of 65 persons each, and four Englehardt collapsible lifeboats measuring 27 ft 5 in (8.4 m) long by 8 ft (2.4 m) wide. The collapsible lifeboats had a capacity of 47 persons each; they had canvas sides, and could be stowed almost flat, taking up a comparatively small amount of deck space. Two were stowed port and starboard on the roof of the officers´ quarters, at the foot of the first funnel, while the other two were stowed port and starboard alongside the emergency cutters.

In her time, Titanic surpassed all rivals in luxury and opulence. She offered an on-board swimming pool, a gymnasium, a Turkish bath, libraries in both the first and second-class, and a squash court. First-class common rooms were adorned with elaborate wood panelling, expensive furniture and other decorations. In addition, the Café Parisien offered cuisine for the first-class passengers, with a sunlit veranda fitted with trellis decorations.

The ship incorporated technologically advanced features for the period. She had an extensive electrical subsystem with steam-powered generators and ship-wide electrical wiring feeding electric lights. She also boasted two Marconi radios, including a powerful 1,500-watt set manned by operators who worked in shifts, allowing constant contact and the transmission of many passenger messages.

Comparisions with Olympic

The Titanic closely resembled her older sister Olympic. Although she enclosed more space and therefore had a larger gross register tonnage, the hull was almost the same length as the Olympic. However, there were a few differences. Two of the most noticeable were that half of the Titanic”s forward promenade A-Deck (below the boat deck) was enclosed against outside weather, and her B-Deck configuration was different from the Olympic. The Titanic had a speciality restaurant called Café Parisien, a feature that the Olympic did not have until 1913. Some of the flaws found on the Olympic, such as the creaking of the aft expansion joint, were corrected on the Titanic. The skid lights that provided natural illumination on A-deck were round; while on Olympic they were oval. The Titanic’s wheelhouse was made narrower and longer than the Olympic’s. These, and other modifications, made the Titanic 1,004 gross register tons larger than the Olympic and thus the largest active ship in the world during her maiden voyage in April 1912.

Maiden Vogage

The ship began her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, bound for New York City, New York, on Wednesday, 10 April 1912, with Captain Edward J. Smith in command. As the Titanic left her berth, her wake caused the liner New York, which was docked nearby, to break away from her moorings, whereupon she was drawn dangerously close (about four feet) to the Titanic before a tugboat towed the New York away. The near accident delayed departure for one hour. After crossing the English Channel, the Titanic stopped at Cherbourg, France, to board additional passengers and stopped again the next day at Queenstown (known today as Cobh), Ireland. Because harbour facilities at Queenstown were inadequate for a ship of her size, Titanic had to anchor off-shore, with boats ferrying the embarking passengers out to her. When she finally set out for New York, there were 2,240 people aboard. John Coffey, a 23 year old crewmember, stowed his way on to a tender by hiding amongst mailbags headed for Cobh. Coffey’s reason for smuggling himself off the Titanic was that he held a superstition about sailing and specifically about traveling on the Titanic, but he later signed to join the crew of the Mauretania.

Some of the most prominent people in the world were travelling in first–class. These included millionaire John Jacob Astor and his wife Madeleine Force Astor; industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim; Macy”s owner Isidor Straus and his wife Ida; Denver millionairess Margaret “Molly” Brown; Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife couturiere Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon; George Elkins Widener and his wife Eleanor; John Borland Thayer, his wife Marian and their seventeen-year-old son, Jack; journalist William Thomas Stead; the Countess of Rothes; U.S. presidential aide Archibald Butt; author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee; author Jacques Futrelle, his wife May, and their friends, Broadway producers Henry and Irene Harris; silent film actress Dorothy Gibson; and others. Also travelling in first–class were White Star Line”s managing director J. Bruce Ismay who came up with the idea for Titanic and the ship”s builder Thomas Andrews, who was on board to observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new ship.

Disaster

Sinking

On the night of Sunday, 14 April, the temperature had dropped to near freezing and the ocean was calm. The moon was not visible and the sky was clear. Captain Smith, in response to iceberg warnings received via wireless over the preceding few days, altered the Titanic”s course slightly to the south. That Sunday at 1:45 PM, a message from the steamer Amerika warned that large icebergs lay in the Titanic”s path, but as Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, the Marconi wireless radio operators, were employed by Marconi and paid to relay messages to and from the passengers, they were not focused on relaying such “non-essential” ice messages to the bridge. Later that evening, another report of numerous large icebergs, this time from the Mesaba, also failed to reach the bridge.

At 11:40 PM while sailing south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, lookouts Fredrick Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted a large iceberg directly ahead of the ship. Fleet sounded the ship”s bell three times and telephoned the bridge exclaiming, “Iceberg, right ahead!”. First Officer Murdoch ordered an abrupt turn to starboard (right) and the engines to be stopped. A collision was inevitable and the iceberg brushed the ship”s starboard side, buckling the hull in several places and popping out rivets below the waterline over a length of 299 ft (90 m). As seawater filled the forward compartments, the watertight doors shut. However, while the ship could stay afloat with four flooded compartments, five were filling with water. The five water-filled compartments weighed down the ship so that the tops of the forward watertight bulkheads fell below the ship”s waterline, allowing water to pour into additional compartments. Captain Smith, alerted by the jolt of the impact, arrived on the bridge and ordered a full stop. Shortly after midnight on 15 April, following an inspection by the ship’s officers and Thomas Andrews, the lifeboats were ordered to be readied and a distress call was sent out.

The first lifeboat launched, boat 7, despite popular belief of a 12:40 AM time, was lowered at 12:27 AM on the starboard side with 28 people on board out of a capacity of 65. Boat 5 was launched two to three minutes later. The Titanic carried 20 lifeboats with a total capacity of 1,178 persons. While not enough to hold all of the passengers and crew, the Titanic carried more boats than was required by the British Board of Regulations. At the time, the number of lifeboats required was determined by a ship”s gross register tonnage, rather than her human capacity.

Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were busy sending out CQD, the international distress signal. Several ships responded, including Mount Temple, Frankfurt and Titanic”s sister ship, Olympic, but none was close enough to make it in time. The closest ship was Cunard Line’s RMS Carpathia 58 miles (93 km) away, which arrived in about four hours—too late to rescue all of Titanic’s passengers. The only land–based location that received the distress call from Titanic was a wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland.

From the bridge, the lights of a nearby ship could be seen off the port side. Not responding to wireless, Fourth Officer Boxhall and Quartermaster Rowe attempted signalling the ship with a Morse lamp and later with distress rockets, but the ship never appeared to respond. The SS Californian, which was nearby and stopped for the night because of ice, also saw lights in the distance. The Californian”s wireless was turned off, and the wireless operator had gone to bed for the night. Just before he went to bed at around 11:00 PM the Californian”s radio operator attempted to warn the Titanic that there was ice ahead, but he was cut off by an exhausted Jack Phillips, who snapped, “Shut up, shut up, I am busy; I am working Cape Race”. When the Californian’s officers first saw the ship, they tried signalling her with their Morse lamp, but also never appeared to receive a response. Later, they noticed the Titanic’s distress signals over the lights and informed Captain Stanley Lord. Even though there was much discussion about the mysterious ship, which to the officers on duty appeared to be moving away, the Californian did not wake her wireless operator until morning.

The Titanic showed no outward signs of being in imminent danger, and passengers were reluctant to leave the apparent safety of the ship to board small lifeboats. As a result, most of the boats were launched partially empty; one boat meant to hold 40 people left the Titanic with only 12 people on board it. With “Women and children first” the imperative for loading lifeboats, Second Officer Lightoller, who was loading boats on the port side, allowed men to board only if oarsmen were needed, even if there was room. First Officer Murdoch, who was loading boats on the starboard side, let men on board if women were absent. As the ship”s list increased people started to become nervous, and some lifeboats began leaving fully loaded. By 2:05 AM, the entire bow was under water, and all the lifeboats, save for two, had been launched.

Around 2:10 AM, the stern rose out of the water exposing the propellers, and by 2:17 the waterline had reached the boat deck. The last two lifeboats floated off the deck, one upside down, the other half filled with water. Shortly afterwards, the forward funnel collapsed, crushing part of the bridge and people in the water. On deck, people were scrambling towards the stern or jumping overboard in hopes of reaching a lifeboat. The ship”s stern slowly rose into the air, and everything unsecured crashed towards the water. While the stern rose, the electrical system finally failed and the lights went out. Shortly afterwards, the stress on the hull caused Titanic to break apart between the last two funnels, and the bow went completely under. The stern righted itself slightly and then rose vertically. After a few moments, at 2:20 AM, this too sank into the ocean.

Only two of the 18 launched lifeboats rescued people after the ship sank. Lifeboat 4 was close by and picked up five people, two of whom later died. Close to an hour later, lifeboat 14 went back and rescued four people, one of whom died afterwards. Other people managed to climb onto the lifeboats that floated off the deck. There were some arguments in some of the other lifeboats about going back, but many survivors were afraid of being swamped by people trying to climb into the lifeboat or being pulled down by the suction from the sinking Titanic, though it turned out that there had been very little suction. In the disaster, first-class men were four times as likely to survive as second-class men, and twice as likely to survive as third-class men. Nearly every first-class woman survived, compared with 86 percent of those in second class and less than half of those in third class.

As the ship fell into the depths, the two sections behaved very differently. The streamlined bow planed off approximately 2,000 feet (609 m) below the surface and slowed somewhat, landing relatively gently. The stern plunged violently to the ocean floor, the hull being torn apart along the way from massive implosions caused by compression of the air still trapped inside. The stern smashed into the bottom at considerable speed, grinding the hull deep into the silt.

Legends and Myths

Unsinkable

Contrary to popular mythology, the Titanic was never described as “unsinkable”, without qualification, until after she sank. There are three trade publications (one of which was probably never published) that describe the Titanic as unsinkable, prior to its sinking, but they all qualify the claim, either with the word practically or with the phrase “as far as possible”. There is no evidence that the notion of the Titanic’s unsinkability had entered public consciousness until after the sinking.

The first unqualified assertion of the Titanic”s unsinkability appears the day after the tragedy (on the 16th of April 1912), in the New York Times, which quotes Philip A. S. Franklin, vice president of the White Star Line as saying, when informed of the tragedy, “I thought her unsinkable and I based by opinion on the best expert advice available. I do not understand it.”

This comment was seized upon by the press and the idea that the White Star Line had previously declared the Titanic to be unsinkable (without qualification) gained immediate and widespread currency.

Rediscovery

The idea of finding the wreck of Titanic, and even raising the ship from the ocean floor, had been around since shortly after the ship sank. No attempts were successful until 1 September 1985, when a joint American-French expedition, led by Jean-Louis Michel (Ifremer) and Dr. Robert Ballard (WHOI), located the wreck. It was found at a depth of 2½ miles, slightly more than 370 miles (600 km) south-east of Mistaken Point, Newfoundland at 41°43′55″N 49°56′45″W / 41.73194, -49.94583Coordinates: 41°43′55″N 49°56′45″W / 41.73194, -49.94583, 13 miles (22 km) from fourth officer Joseph Boxhall”s last position reading where Titanic was originally thought to rest. Ballard noted that his crew had paid out 12,500 ft (3,800 m) of the submersible”s cable at the time of the discovery of the wreck, giving an approximate depth of the seabed of 12,450 ft. Ifremer, the French partner in the search, records a depth of 3,800 m, an almost exact equivalent. This approximates to 2⅓ miles, often rounded upwards to 2½ miles.

Ballard had in 1982 requested funding for the project from the US Navy, but this was provided only on the condition that the first priority was the search for the sunken US submarines Thresher and Scorpion. Only when these had been discovered and photographed did the search for Titanic begin.

The most notable discovery the team made was that the ship had split apart, the stern section lying 1,970 feet (600 m) from the bow section and facing opposite directions. There had been conflicting witness accounts of whether the ship broke apart or not, and both the American and British inquiries found that the ship sank intact. Up until the discovery of the wreck, it was generally assumed that the ship did not break apart.

The bow section had struck the ocean floor at a position just under the forepeak, and embedded itself 60 feet (18 m) into the silt on the ocean floor. Although parts of the hull had buckled, the bow was mostly intact. The collision with the ocean floor forced water out of Titanic through the hull below the well deck. One of the steel covers (reportedly weighing approximately ten tonnes) was blown off the side of the hull. The Bow is still under tension, in particular the heavily damaged and partially collapsed decks.

The stern section was in much worse condition, and appeared to have been torn apart during its descent. Unlike the bow section, which was flooded with water before it sank, the it is likely that the stern section sank with a significant volume of air trapped inside it. As it sank, the external water pressure increased but the pressure of the trapped air could not follow suit due to the many air pockets in relatively sealed sections. Therefore, some areas of the stern section”s hull experienced a large pressure differential between outside and inside which possibly caused an implosion. Further damage was caused by the sudden impact of hitting the seabed; with little structural integrity left, the decks collapsed as the stern hit.

Surrounding the wreck is a large debris field with pieces of the ship, furniture, dinnerware and personal items scattered over one square mile (2.6 km²). Softer materials, like wood, carpet and human remains were devoured by undersea organisms.

Dr. Ballard and his team did not bring up any artifacts from the site, considering this to be tantamount to grave robbing. Under international maritime law, however, the recovery of artifacts is necessary to establish salvage rights to a shipwreck. In the years after the find, Titanic has been the object of a number of court cases concerning ownership of artifacts and the wreck site itself. In 1994, RMS Titanic, Inc. was awarded ownership and salvaging rights of the wreck, even though RMS Titanic Inc. and other salvaging expeditions have been criticized for taking items from the wreck.

Approximately 6,000 artifacts have been removed from the wreck. Many of these were put on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, and later as part of a traveling museum exhibit.

Current condition of the wreck

Many scientists, including Robert Ballard, are concerned that visits by tourists in submersibles and the recovery of artifacts are hastening the decay of the wreck. Underwater microbes have been eating away at Titanic”s iron since the ship sank, but because of the extra damage visitors have caused, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that “the hull and structure of the ship may collapse to the ocean floor within the next 50 years.”

Ballard’s book Return to Titanic, published by the National Geographic Society, includes photographs depicting the deterioration of the promenade deck and damage caused by submersibles landing on the ship. The mast has almost completely deteriorated and has been stripped of its bell and brass light. Other damage includes a gash on the bow section where block letters once spelled Titanic, part of the brass telemotor which once held the ship”s wooden wheel is now twisted and the crows nest has now completely deteriorated.

Ownership

Titanic’s rediscovery in 1985 launched a debate over ownership of the wreck and the valuable items inside. On 7 June 1994, RMS Titanic Inc., a subsidiary of Premier Exhibitions Inc., was awarded ownership and salvaging rights by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Since 1987, RMS Titanic Inc. and its predecessors have conducted seven expeditions and salvaged over 5,500 historic objects. The biggest single recovered object was a 17-ton section of the hull, recovered in 1998. Many of these items are part of travelling museum exhibitions.

In 1993, a French administrator in the Office of Maritime Affairs of the Ministry of Equipment, Transportation, and Tourism awarded RMS Titanic Inc”s predecessor title to the relics recovered in 1987.

In a motion filed on 12 February 2004, RMS Titanic Inc. requested that the district court enter an order awarding it “title to all the artifacts (including portions of the hull) which are the subject of this action pursuant to the Law of Finds” or, in the alternative, a salvage award in the amount of $225 million. RMS Titanic Inc. excluded from its motion any claim for an award of title to the objects recovered in 1987, but it did request that the district court declare that, based on the French administrative action, “the artifacts raised during the 1987 expedition are independently owned by RMST.” Following a hearing, the district court entered an order dated 2 July 2004, in which it refused to grant comity and recognize the 1993 decision of the French administrator, and rejected RMS Titanic Inc.’s claim that it should be awarded title to the items recovered since 1993 under the Maritime Law of Finds.

RMS Titanic Inc. appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. In its decision of 31 January 2006 the court recognized “explicitly the appropriateness of applying maritime salvage law to historic wrecks such as that of Titanic” and denied the application of the Maritime Law of Finds. The court also ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction over the “1987 artifacts”, and therefore vacated that part of the court’s 2 July 2004 order. In other words, according to this decision, RMS Titanic Inc. has ownership title to the objects awarded in the French decision (valued $16.5 million earlier) and continues to be salver-in-possession of Titanic wreck. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District Court to determine the salvage award ($225 million requested by RMS Titanic Inc.).

Useful Links

Discover more from LandmarkLocation.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.